Beer has been the most consumed alcoholic beverage in the United States for the past 20 years. Over the past 40 years, the beer manufacturing industry has undergone a quiet revolution, despite the initial doubts of industry experts.

Prior to prohibition, the influx of German immigrants into the country brought a preference for lagers, and brewery consolidation eliminated the majority of smaller-operations which produced different varieties. The passage of the 18th Amendment, which eliminated alcohol production in the country, was the proverbial nail in the coffin for independent brewers. When prohibition was finally repealed, the largest breweries took advantage of their superior technology and efficiency to push the small brewers out of business. Thus by the early 1980s it is estimated that there were fewer than 100 breweries operating in the United States, almost all of which produced beer of a similar style—a light, somewhat bland, lager known as “American Lager.”

Homebrewing would be the spark that would eventually change the face of beer production. Independent small breweries began cropping up throughout the country, trying to bring back styles of beer that had been effectively wiped out by industry monopolization. Collaboration amongst small-scale beer manufacturers provided the necessary brewing knowledge to give small regional breweries the opportunity to compete with the large manufacturers. Advancements in communications technology, such as the advent of the personal computer, allowed long distance consultation, which further spurred the accessibility of craft brewing to the common man. Today, 99 percent of breweries in the United States are small craft breweries, and The Brewers Association has rigorously standardized 142 styles of beer. In accordance with this, American tastes are also trending towards the consumption of more varied and robust styles of beer. In fact, the average American now resides within 10 miles of a brewery. As of 2015 there are 124 craft breweries in Virginia, up roughly 59 percent from 2014.

So with so many craft breweries around to try, what should you expect when drinking craft beer? Obviously most craft beer does not resemble ubiquitous traditional American lager. Beer styles have been influenced throughout the history of beer production by a variety of factors, including locale, ingredient availability, and economic and political restrictions. At its essence, beer is made up of three main ingredients: malt, hops, and water. Malt serves as the base of beer, and is the mix of malted grains – usually barley – that is fermented to create sugar, and thereby, alcohol. Hops are a flavoring agent and preservative that is used to balance the taste of beer, providing bitterness in contrast with the sweeter flavor of the malt. Beer is divided into two categories, ales and lagers, based on the type of yeast used in the fermentation process. Ales are fermented with yeast that rises to the top of the brew at higher temperatures, whereas lagers are fermented for longer periods with yeast that remains at the bottom. The resulting difference is that ales have a tendency to be stronger both in flavor and alcohol content than lagers, and lagers tend to be less cloudy in appearance than ales.

The following serves as a guide to some of the more commonly found families of beer styles, within which there are many subcategories. Although this list is far from exhaustive, it provides background information regarding some of the more basic styles you might encounter when venturing out to your local brewery.

Pilsners/Pale Lagers

Pilsners/Pale Lagers

Pilsners are the original pale, light, hoppy brew style. Originating in Germany and the Czech Republic, Pilsners are crisp, clean lagers with a bready malt flavor.

Dark Lagers

Using darker malt than their paler counterparts, dark lagers are toasty and caramel-like in flavor. Common styles include the German-style Märzen/Oktoberfest and Vienna lager, which have proven very popular among American consumers.

Bocks

Traditionally, Bocks include little to no hops, and are therefore sweeter than most dark lagers. Doppelbocks are stronger in flavor and are a more alcoholic version of the original Bock, given the German literal meaning as “Double Bock.” Trippelbocks (English: Triple Bock) are a less common, but definitively stronger version of the double variety. Certain styles of Bock may include wheat (Weizenbock) or additional hops (Maibock).

IPAs

Commonly referred to by the acronym “IPA” India Pale Ales are the top selling craft beer style in the United States. IPAs were invented in order to create a beer that would survive the long trip to India for consumption by British soldiers, as India’s climate was too hot to lend itself to brewing. The addition of extra hops, which function as preservatives, created a beer that not only survived the journey, but was believed to actually have improved flavor. IPAs can possess a floral, citrus, or even piney flavor, depending on the type of hops used. Much like Bocks, a stronger variety of IPAs exist known as DIPAs, or Double IPAs.

Porters/Stouts

Porters/Stouts

Porters and Stouts comprise the two darkest styles of craft beer currently available. The difference between them is widely contested, and various distinctions in history, composition, and brewing methodology have been proposed as potential divisions between the two. The common consensus is that Porters are made from malted barley, whereas Stouts consist of unmalted, roasted barley. Though historical context may refute this differentiation, this belief largely defines how modern brewers choose to name, and thus distinguish their beers. Dark and roasty Porters have light aspects of chocolate, nut, and coffee flavors, but are less dramatic than their more espresso-like cousins, Stouts. Stouts can range from a sweeter and maltier Milk Stout to a more bitter and alcoholic Imperial Stout.

Wheat Beer

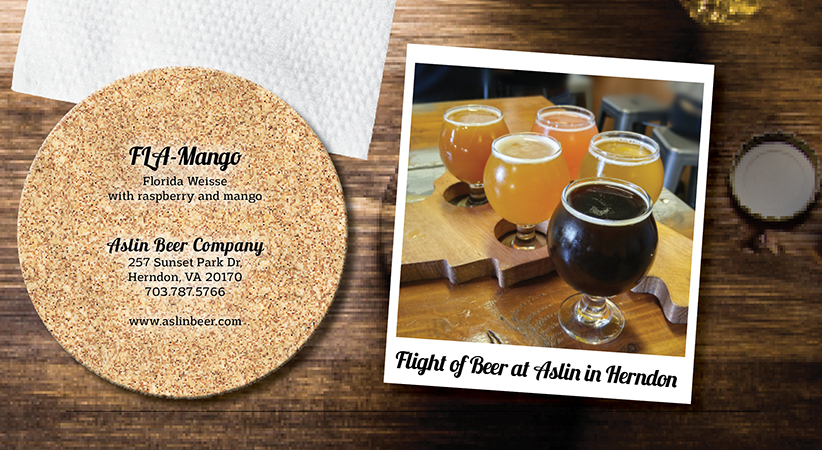

In 1516, Germany passed a law known as Reinheitsgebot, also known as the German Beer Purity Law, which dictated that the only ingredients permitted in the manufacturing of bottom-fermented beer (lagers) were water, barley, and hops. The law was enacted in an attempt to prevent breweries from competing for grains needed to produce bread, namely wheat and rye. As time passed, yeast was recognized by the law as a necessity for beer fermentation and was exempted from the restriction. Reinheitsgebot still remains in effect in Germany today and there are therefore limited wheat-based beers exported from Germany. Top-fermented beers (ales), however, saw more relaxed restrictions and certain beers styles, such as the Hefeweizen survived. Outside of Germany, Belgian Witbeir and American varieties of wheat-inclusive brews have flourished in recent times. Modern wheat beers generally use anywhere between 40-60 percent wheat in the brewing process. Wheat gives the beer a creamier and tangier flavor, which lends to the addition of fruit flavors. Due to this, you will frequently come across wheat beers that include fruit in the brewing process.

Hybrids

One of the beauties of the craft beer movement is that although certain styles are standardized for the sake of differentiation and better understanding of the brewing process, experimentation is very much encouraged. Fruits, spices, and deviations from traditional fermentation methods can create entirely new styles of the world’s most consumed beverage. A very common example of this is the Kölsch, which is a pale ale that is warm fermented, and then conditioned at cold temperatures like a lager.

And there you have it—a very basic guide to the quickly expanding world of craft brewing! Have no fear, the craft brewing world is very focused on open discourse, so if you have any questions, just ask your server or brewer.